Iran: Protests Lend Momentum To Students' Struggle

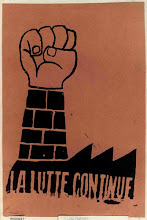

Iran: Protests Lend Momentum To Students' StruggleStudent pressure, like this rally at Tehran University, began building in October

(Fars)

(Fars)

They may not be quite like the heady student protests of years past. But fresh rallies and a flurry of arrests in Iran suggest that the country's student movement is gaining steam for yet another push for change in the Islamic republic.

Student rallies began to gain momentum in early December. But they appear to be part of a wave of open dissent that began to build in earnest one year ago when -- during a speech by Mahmud Ahmadinejad at Tehran University -- students in the crowd burned photos of the president and chanted, "Death to the dictator!" Similar, if less strident, rallies followed in May and October, with the authorities responding in each case by arresting activists.

On December 4, some 250 students at Tehran University gathered to chant slogans such as “Freedom and Equality!” and “No to war!” About 20 were arrested and sent to Tehran's Evin prison. Several were released but others are still being held, students say. Similar protests spread the next day to the cities of Hamadan, Isfahan, Mazandaran, Shiraz, and Kerman, where students reportedly openly criticized Iran’s disputed nuclear program.

"Since the academic year began in October, the students' movements and activities have not stopped,” Iraj Jamsheedi, an independent journalist, told RFE/RL from Tehran. “They’ve been ongoing, at different levels, at many universities across the country. It has become a trend. And unlike in the past, I don't think their activities will die down after a short while, because their demands reflect those of the majority of the Iranian people."

"Since the academic year began in October, the students' movements and activities have not stopped,” Iraj Jamsheedi, an independent journalist, told RFE/RL from Tehran. “They’ve been ongoing, at different levels, at many universities across the country. It has become a trend. And unlike in the past, I don't think their activities will die down after a short while, because their demands reflect those of the majority of the Iranian people."

'Happy Events'

Authorities had not planned any official events at universities to mark Student Day, which commemorates the death of three students during protests in 1953. That is in sharp contrast to previous years when senior leaders, including Ahmadinejad, made a point of meeting with students. Iranian media said the authorities this year instead planned "happy events" for students, such as "placing flowers on martyrs’ graves."

The students had different plans.

Student Day this year fell at the start of the Muslim weekend on December 7, so organizers were expected to mount rallies on December 9.

Iran's Intelligence Ministry on December 8 reported detaining several people whom it accused of carrying false student-identification cards and planning an "illegal gathering" at Tehran University. The ministry alleged that the detainees were plotting "to create conflict, disturbances, and unrest" at the behest of "antigovernment groups."

An unspecified number of students with ties to the Office to Foster Unity (Daftar-e Tahkim-e Wahdat), a leading reformist students' group, gathered at Tehran University on December 9 to protest the detention of their colleagues. A report by Reuters said photographs from the rally indicated protesters demanding the release of student detainees had damaged bars on one of the university's gates.

Bahar Hedayat, a member of the women's commission of the Office to Foster Unity, had predicted ahead of Student Day that young people would protest. She said they would “demand their rights, including the right to academic freedom and publish journals reflective of their opinions. They also demand freedom for political and social organizations." Hedayat, speaking to RFE/RL from Tehran, said students also are calling more broadly for democratic change, improved human rights, and the release of students imprisoned for taking part in demonstrations.

Imprisoned Youth

Parents and relatives of students detained last week in Tehran were still seeking information about the fate of their children held at Evin prison. Nasreen Musavi told RFE/RL's Radio Farda that her daughter, Ilnaz, had been arrested during the protest on December 4 and that the authorities had denied her any contact with her family or a lawyer. Another student, Ehsan Azadbar, said he was arrested during the rally along with his sister Azadeh, and that the authorities had released him only after two days of interrogation. Azadeh remains in custody.

At least one student has been in prison since 1999. That year, Iran saw its largest student demonstrations since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Thousands took part in demanding freedom. Clashes with police left five students dead. Similar scenes, on a smallar scale, were seen in 2003. With some shouting “Death to Khamenei!,” the supreme leader who holds ultimate religious and political power under the constitution, thousands rallied against the perceived slow pace of change under then-President Mohammad Khatami, a reformist. Scores were arrested after clashes with police and radical Islamist vigilantes.

As the authorities sharpen their current crackdown, Hedayat says that she and other students know they risk arrest, expulsion from school -- even death for campaigning for change against the country's current leadership. “The more active the student movements become, the more intense will become the pressure from the authorities,” Hedayat said.

But the latest protests will continue, she vowed, because Iranians "can no longer put up with the current political, economic, and social pressures."

Authorities had not planned any official events at universities to mark Student Day, which commemorates the death of three students during protests in 1953. That is in sharp contrast to previous years when senior leaders, including Ahmadinejad, made a point of meeting with students. Iranian media said the authorities this year instead planned "happy events" for students, such as "placing flowers on martyrs’ graves."

The students had different plans.

Student Day this year fell at the start of the Muslim weekend on December 7, so organizers were expected to mount rallies on December 9.

Iran's Intelligence Ministry on December 8 reported detaining several people whom it accused of carrying false student-identification cards and planning an "illegal gathering" at Tehran University. The ministry alleged that the detainees were plotting "to create conflict, disturbances, and unrest" at the behest of "antigovernment groups."

An unspecified number of students with ties to the Office to Foster Unity (Daftar-e Tahkim-e Wahdat), a leading reformist students' group, gathered at Tehran University on December 9 to protest the detention of their colleagues. A report by Reuters said photographs from the rally indicated protesters demanding the release of student detainees had damaged bars on one of the university's gates.

Bahar Hedayat, a member of the women's commission of the Office to Foster Unity, had predicted ahead of Student Day that young people would protest. She said they would “demand their rights, including the right to academic freedom and publish journals reflective of their opinions. They also demand freedom for political and social organizations." Hedayat, speaking to RFE/RL from Tehran, said students also are calling more broadly for democratic change, improved human rights, and the release of students imprisoned for taking part in demonstrations.

Imprisoned Youth

Parents and relatives of students detained last week in Tehran were still seeking information about the fate of their children held at Evin prison. Nasreen Musavi told RFE/RL's Radio Farda that her daughter, Ilnaz, had been arrested during the protest on December 4 and that the authorities had denied her any contact with her family or a lawyer. Another student, Ehsan Azadbar, said he was arrested during the rally along with his sister Azadeh, and that the authorities had released him only after two days of interrogation. Azadeh remains in custody.

At least one student has been in prison since 1999. That year, Iran saw its largest student demonstrations since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Thousands took part in demanding freedom. Clashes with police left five students dead. Similar scenes, on a smallar scale, were seen in 2003. With some shouting “Death to Khamenei!,” the supreme leader who holds ultimate religious and political power under the constitution, thousands rallied against the perceived slow pace of change under then-President Mohammad Khatami, a reformist. Scores were arrested after clashes with police and radical Islamist vigilantes.

As the authorities sharpen their current crackdown, Hedayat says that she and other students know they risk arrest, expulsion from school -- even death for campaigning for change against the country's current leadership. “The more active the student movements become, the more intense will become the pressure from the authorities,” Hedayat said.

But the latest protests will continue, she vowed, because Iranians "can no longer put up with the current political, economic, and social pressures."

No comments:

Post a Comment